Open 7 days 10am - 5pm

Adults: $15

Under 16 & Diggers Club Members: Free

Garden Stories

By Jeremy Francis

On Revisiting Hidcote

January, 2026

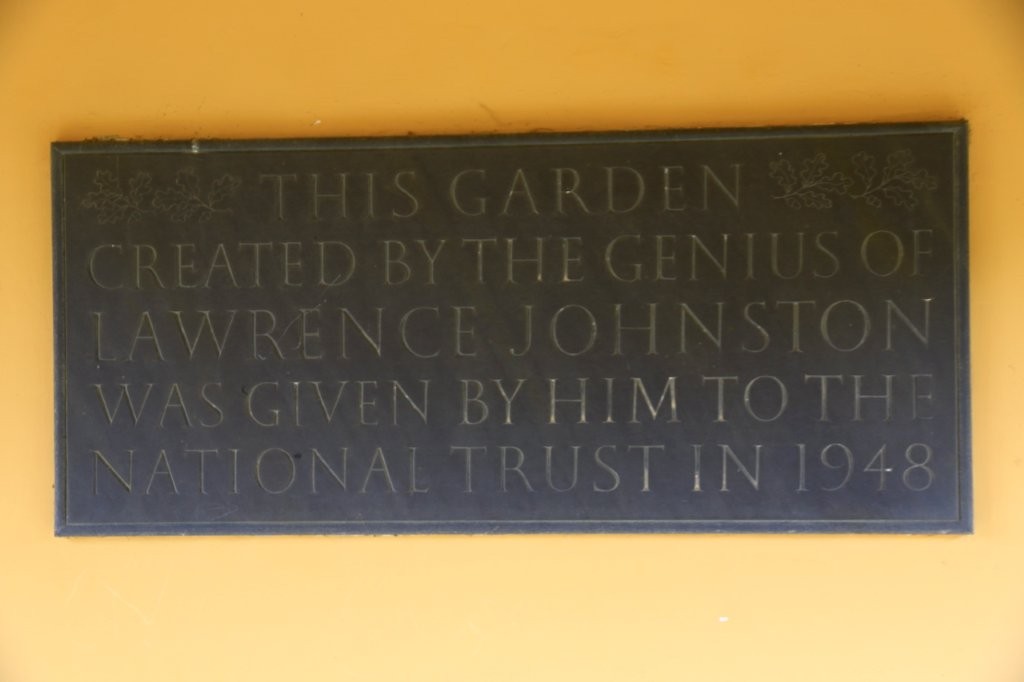

Over (very many) years now, Valerie and I have been back to Hidcote (near Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds) several times. Our first visit was in 1981, and we were back in 1988, then I was there again in 2007 on a gig with Botanica Tours of the 'Great Gardens of southern England, and Valerie and I visited yet again in June of 2024.

I suppose, for me, Hidcote ranks in the top dozen of English gardens, and is the best two or three of the Arts and Crafts Gardens of that golden age of garden making from late Victorian times through to WW2. In fact, I was busily studying my books on Hidcote as we were laying out Cloudehill in 1992. Our main terrace is the same length as Hidcote's to within a couple of metres. This was a coincidence, something I noticed as we were finishing the terrace. On the other hand, perhaps not entirely coincidental in that both the Cloudehill and Hidcote terraces have some half dozen 'garden rooms' from one end to the other and each of these needed to be of a size proportional to the overall structure of the garden. Indeed our 'warm borders' are exactly the same size as Hidcote's 'Red Borders', their length and their depth, as much as I could make them.

Above we have a general view of the 'cottage garden' with sun lovers in softer colours. Hidcote's manor I suppose is 3 - 400 years old and typical of the manors everywhere in the Cotswolds though perhaps a little smaller the most. In the good old days, the Cotswolds were famous for their sheep, the 'Cotswolds Lions'. The people of these gentle hills grew rich exporting their wool to the Low Countries, what are now Belgium and Holland, back in the Middle Ages and Tudor times. In fact doing exactly what most Australian farmers were doing from settlement through to the collapse in the wool market in 1990. I might add I ran several thousand merinos back in farming days and still have a great fondness for them.

Nowadays one enters Hidcote via the manor house and much more civilized than our visits in the '80s when everyone was wandering in via a side route which looked a bit like the trade men’s entrance.

Once in, immediately one has a view along the main terrace with the old cedar of Lebanon to the right. This tree is the one tree the maker of Hidcote, Major Lawrence Johnston, inherited from the previous owner as he began measuring out his garden in 1907. I reckon now it is well on its way to 200 years old. That's the thing about Cedrus libani. They only really hit their straps when at least 150 years old. One of those trees one plants for one's great great great grandchildren, but worth it.

The other thing to be noticed as one walks, every little while there are gardens diverting attention to the side. Here we have one packed with box-edged beds planted to dry-tolerant plants.

Below we have another garden with recently clipped topiary around paving. Now are these yew or box? I suspect yew, though in this photo they look a bit more like box. Sadly, box is being knocked around severely by 'box blight' in the UK. Many old topiary specimens are being dug out and replaced by specimens made out of a dwarf yew, which, as I'm sure you appreciate, looks very similar. However, generally yew is clipped towards the end of summer, not the beginning. I'll have to go back and find out which these are.

To the rear is the cedar again, partly masking Hidcote's lovely little manor house.

And looking back along the main terrace to the cedar with early perennials at their finest. One might notice the path along this terrace is grass. Using turf for this path is both a joy and a problem which I will discuss as we go.

The next 'room' along the path, the 'circle garden'. A goodly area of grass lapped by beds planted to the old French 'Rouen lilac'. David Glenn gave me a couple of these difficult-to-get-hold-of plants as a memento of Hidcote, and the one surviving is powering away amongst the viburnums near the entrance to the upper meadow at Cloudehill.

I look at this photo and cannot help thinking the gardeners are about to launch into a minuet. Perhaps working at Hidcote does that for you?

The next room, the famous red borders. In fact, red and orange and green and purple borders. I did try copying this scheme back in 1994 and the result was simply awful. Nowadays I use lots of lots of yellow, strong blue, even some darkish crimson in our warm borders. I am finding the more colour the better. And especially as the eight deep-green Chinese plum yews on each side of the central path have filled in their spots.

My understanding is that the famous rosarian, Graham Stuart Thomas, in his advisory work for the English National Trust from the 1950s to the '70s, was the one largely responsible for perfecting Hidcote's red borders intensely colourful yet austere scheme. I might say also I have never seen a border anything like remotely restrictive in its choice of colour, and successful, in any other garden. Johnston worked on perfecting this colour scheme at Hidcote for more than 30 years, and then Graham Stuart Thomas for a period not far short of this. Both rank as among the very finest horticulturalists of their respective generations. One should not try and copy them.

A detail of the red borders showing hemerocallis, a crocosmia (which would have been C. Lucifer in the ’80s but I think this one is more recent) and behind a buddleia which is probably B. ‘Black Knight’. (I imported Black Knight into Australia especially in 1988 on the strength of seeing it at Hidcote, and of course it was already in Oz) and also some purple smoke bushes and clumps of Miscanthus.

A minor garden to the side of the main axis, narrow brick paths, box hedges, leading to the pool garden.

I think originally this pool was set down at ground level, however, raised to its present height to enable the children from Kiftsgate Court (a short distance away, and a garden I will cover next time) to, in theory, swim, though it is still so shallow I expect mostly they were paddling. The interesting thing is the way the pool entirely uses all the space in this compartment, the paths around it are very narrow. And also the way it acts as a mirror to the sky. To see this properly, one needs to visit on a day with broken cloud, and plenty of blue amongst the white, which was not the case on this occasion.

Now how many of these things did Johnston have in mind as he was constructing this part of Hidcote? And how much was entirely serendipitous? And here I have to put up my hand to admit serendipity has a huge part to play in gardening.

Through the yew archway, the path leads on to wilder parts of the garden. Notice the paving, slithers of stone laid on edge. And the hydrangeas to each side opening the first of their dusty mauve flowers. These are more or less the hydangea we grow as H. aspera Strigosa. This is a particularly lovely thing and, despite its delicate appearance, for us tolerates a surprising amount of direct sun.

An important path set at right angles to the main axis and connecting with it via one of the twin garden pavilions (in the distance). I should be saying 'spoiler alert' at this point. Walking along the axis and suddenly spotting how one pavilion acts as a gateway to a major garden to one side is one of the great moments in gardening. I once watched a bloke with a very fancy camera equipped with a hefty telephoto lens climbing the steps between the pavilions from the red borders, draw level with this pavilion, then swing his camera up and take a shot in all of one second as though the scene in front of him might vanish forever into some mid-summer's afternoon's dream world if he took any longer over taking his shot. It was one of the funniest things I have seen and the bloke immediately lowered his camera and burst out laughing himself.

Harold Nicolson (one of the designers of Sissinghurst, along with his wife Vita Sackville-West) spoke of the importance of incorporating 'expectation and surprise' into the structure of the gardens. Of course, Sissinghurst has plenty of this but nothing quite as astonishing as Hidcote's hidden axis.

A stone bridge over the tiny stream that actually originates in Hidcote. A handy thing to have, and an excuse to plant its banks with semi-aquatics. The range of plants in Hidcote is colossal. Johnston was an example of plant collector also with a serious passion for garden design. They are a rare breed and there have only ever been a handful. And, typical of Johnston, when one stands in the pavilion looking along this path, he has made his bridge vanish below the level of the path to each side of the structure. The bridge in effect is a kind of 'haha'. The only one I have ever seen.

One of the pavilions. Narrow red-pink bricks, Cotswold stone roof tiles and handsome stone finial.

The near corner of the left-hand border was planted with a Pinus mugo in the 1980s which was old enough to completely fill the space. It seemed a bit anomalous and interesting to see at some point it was removed. Probably the pine was planted by Major Johnston himself and everyone hesitated for a very long time to nip it out. Decisions like this can become quite a quandary in an important National Trust garden.

The other thing I think about as I look at this photo - when setting out Cloudehill, none of my several plans of Hidcote included where north lay. I presumed this axis ran north-south to provide equal amounts of sunshine to both borders. That, certainly, is why the Cloudehill borders run north-south. And they work well. All the flowers face either the morning sun or the afternoon sun and towards the path for visitors to enjoy. Eventually a book was published which included a plan of Hidcote showing where north was and, blow me, their borders run east-west. Now the beauty of east-west borders is that they look stunning beyond compare in low morning and evening light, which is when Claire Takacs takes all her amazing and prize-winning photos but is something which never quite happens. The problem this makes for Hidcote though is to balance the shady border with the sunny border. Something to keep gardeners like this one on their toes.

One walks through the pavilion, turns to the right and this is the view.

Much of the glory of Hidcote is that path along the main axis is grass. As you can see in the photo above, green grass shows off the Red Border’s colour scheme to perfection. Now Hidcote was set out by Major Johnston with the thought only one or two hundred might be walking along this path in any one summer whereas, nowadays, some 130,000 people come to see. And 130,000 walking along this path in an average English summer will turn all this grass to mud, and hence the rope across it. In the times I have visited, I only remember walking from one end of the main axis to the other once. Visiting in 2024, we found signs directing visitors on a rather circuitous zigzag route backwards and forwards ACROSS Hidcote’s spectacular axis in a way to keep the grass pristine and not in a way to allow visitors to inspect the plants. A very great shame and another example of the difficulties of converting what was once a very private garden into a very public one. These thoughts in mind, I paved the path on Cloudehill’s main terrace with brick and cobblestones, hoping to give the impression of hall rug flung down between the flowers.

Valerie standing at the gate at the far end of this axis. In the instance of Cloudehill, our axes are terminated with little pavilions, as beyond there is forest. I do envy Hidcote with its hilltop site and views running for miles in all directions. This is known as Heaven's Gate.

Some metres past the gate is a haha with uninterrupted views across farmland to the Vale of Evesham.

Hidcote's theatre. A very simple rectangle of grass with a raised circular stage area, with three beech, I think, using up much of the area.

The Arts and Crafts gardens I believe were heavily influenced by the old Italian renaissance gardens of the 1560s to the 1640s. They also had a great deal of structure and nearly all had theatres. Villa D’Este and Villa Lante are famous examples. There are a number of 'green' theatres in England, but Hidcote's is one of the more notable. Do admire the cedar to the right.

Hidcote's theatre is in the middle of the garden and the two dozen or so garden compartments making up Hidcote's garden circle around this spacious area. On the far side of the main axis from the theatre is Hidcote's pillar garden. Slightly past its best in this shot but the yew pillars showing just how useful topiary can be in providing bones to an otherwise amorphous planting.

Valerie and one of our hosts, Elaine Drage, exploring 'Mrs Winthrop's garden. This is easy to miss, a semi-secret garden in a sunny spot planted in blue and yellow flowers by Johnston for his mother.